Why Masking (Autism) is Exhausting

As a therapist, one of the topics that comes up often in conversations with clients who have Autism is masking. If you’re not familiar with the term, masking is the process of hiding, suppressing, or camouflaging autistic traits to fit into social environments that are built for neurotypical people.

On paper, it might sound like just another form of “adapting” or “social skills.” But in reality, masking is much more than that. It’s a constant, high-effort performance — and it can be incredibly draining.

So let’s dig into why masking is exhausting, what research tells us about its impact, and why creating spaces where people don’t need to mask is essential for mental health and well-being.

What is Masking?

Masking is essentially when an autistic person changes how they naturally behave to appear “neurotypical.” This can include:

- Forcing or suppressing facial expressions, tone of voice, or gestures.

- Imitating the social behaviours of peers (like scripted jokes, nodding at certain times, or rehearsed small talk).

- Suppressing stimming (hand flapping, rocking, tapping, etc.) even when it helps with regulation.

- Forcing eye contact, even if it feels uncomfortable.

- Carefully monitoring speech — tone, volume, pace — to blend in.

Some autistic folks describe masking as “acting,” while others say it feels like putting on a costume or a heavy armour. The goal isn’t necessarily to deceive but to survive socially in a world that often punishes or stigmatizes difference.

Why Do People Mask?

Masking doesn’t come out of nowhere — it’s a survival strategy.

Many autistic people learn early on (sometimes before they even have language for it) that their natural behaviours are not accepted or understood. Maybe they’ve been teased for stimming, told they’re “too blunt,” or criticized for not making eye contact.

Over time, masking becomes a way to reduce bullying, avoid discrimination, or secure opportunities like jobs, friendships, and romantic relationships. Research suggests that women and gender-diverse autistic people, in particular, may feel extra pressure to mask, since social expectations are different across genders.

Masking can be protective in the short term. It may help someone get through a job interview or a difficult social event. But the cost of constant masking adds up — mentally, emotionally, and even physically.

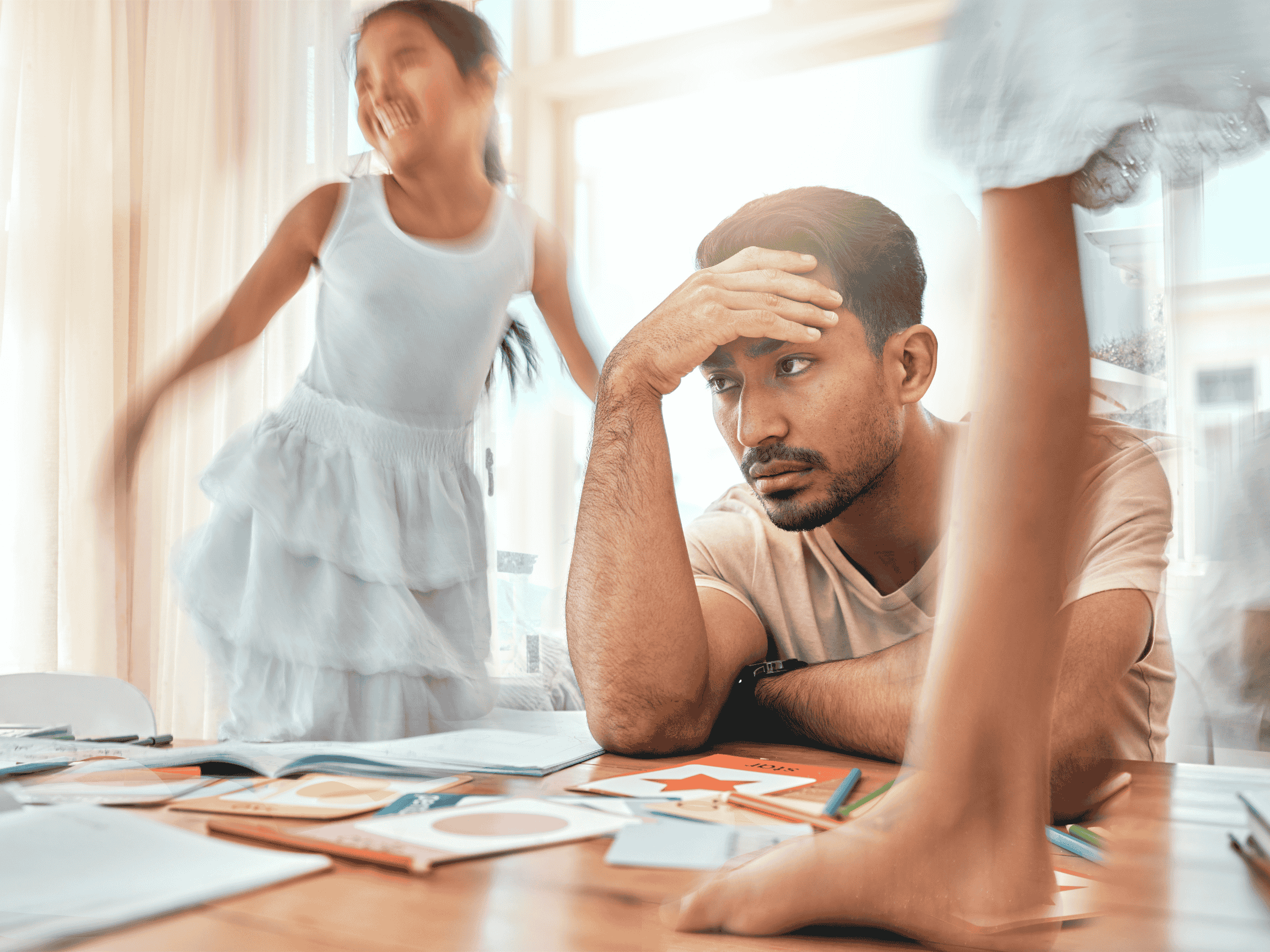

Why Masking is Exhausting

1. Constant Self-Monitoring

Masking means running mental “tabs” at all times: Am I making enough eye contact? Did I laugh at the right moment? This level of surveillance drains mental and emotional energy.

2. Suppression of Natural Coping

Behaviours like stimming or avoiding eye contact aren’t flaws — they’re regulation tools. Masking forces people to suppress these, leaving stress unprocessed.

3. Emotional Disconnect

Social interactions feel scripted rather than authentic, which creates loneliness and isolation.

4. Burnout and Exhaustion

Masking contributes to autistic burnout — a state of extreme physical, mental, and emotional depletion linked to skill loss, reduced executive functioning, and even physical illness.

5. Mental Health Risks

Masking is strongly associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidality. When the real self feels “unacceptable,” self-esteem suffers.

The Double Bind of Masking: Both Protection & Risk

Here’s where it gets complicated: masking can sometimes feel necessary. For example, masking in a job interview might increase someone’s chances of getting hired, which is important for survival.

But the very act of masking long-term creates its own set of risks. It’s a double bind — needing to mask to avoid discrimination while also being harmed by the act of masking itself.

This is why simply telling autistic people to “just unmask and be yourself” isn’t realistic. The problem isn’t the individual choosing to mask; it’s the social structures and environments that make masking feel like the only safe option.

How to Reduce Masking Exhaustion

1. Safe Spaces to Unmask

Home, therapy, or supportive communities can provide freedom to stim, rest, or communicate without judgment.

2. Validation and Education

Learning that masking has a name — and that it’s common — can help reduce shame and increase self-understanding.

3. Systemic Advocacy

Schools, workplaces, and communities need to become more neurodiversity-affirming: sensory-friendly environments, flexible communication, and policies that reduce ableism.

4. Therapeutic Support

Therapy isn’t about forcing someone to unmask everywhere. Instead, it helps people explore when masking feels necessary, when it’s safe to let go, and how to advocate for their needs.

A Personal Note

As a therapist, I’ve witnessed firsthand how heavy the cost of masking can be. Clients often describe it as carrying an invisible backpack full of bricks — one that nobody else can see, but that shapes every decision, every interaction, every day.

And here’s the thing: the exhaustion people feel from masking isn’t weakness. It’s the very real outcome of living in a world not designed with neurodivergent people in mind.

The conversation about masking needs to shift from “Why can’t autistic people just be themselves?” to “Why isn’t the world safe enough for autistic people to be themselves?”

Because the truth is, everyone deserves to exist authentically — without having to hide their identity just to survive.

Key Takeaways

- Masking = camouflaging autistic traits to fit in.

- It’s exhausting because it requires constant monitoring, suppresses natural coping, and disconnects people from their authentic selves.

- Long-term masking increases risks for burnout, anxiety, and depression.

- The solution isn’t individual — it’s systemic. We need safer, more inclusive spaces that don’t demand masking.

Everyone deserves to live authentically without needing to hide who they are just to survive.

Cage, E., & Troxell-Whitman, Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899–1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x

Cassidy, S., Bradley, L., Robinson, J., Allison, C., McHugh, M., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2018). Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger's syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: A clinical cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(2), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70248-2

Hull, L., Mandy, W., & Petrides, K. V. (2017). Behavioural and cognitive sex/gender differences in autism spectrum condition and typically developing males and females. Autism, 21(6), 706–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316669087

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2019). The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: A narrative review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(4), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00197-9

Raymaker, D. M., Teo, A. R., Steckler, N. A., Lentz, B., Scharer, M., Delos Santos, A., ... & Nicolaidis, C. (2020). “Having All of Your Internal Resources Exhausted Beyond Measure and Being Left with No Clean-Up Crew”: Defining Autistic Burnout. Autism in Adulthood, 2(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0079

.png)